Can Being Underweight Affect Fertility? What Research Shows

Mona Bungum

Article

8 min

A clear, evidence-based guide to how low body weight and restrictive eating can affect fertility, ovulation, pregnancy outcomes, and long-term child health.

Many women are surprised when pregnancy does not happen despite feeling healthy. They may exercise regularly, eat carefully, and receive positive feedback about their body or lifestyle. When fertility challenges arise, the idea that being too thin or not eating enough could play a role can feel confusing, or even upsetting. For women asking whether being underweight affects fertility, the question is often wrapped in self-doubt rather than clear information.

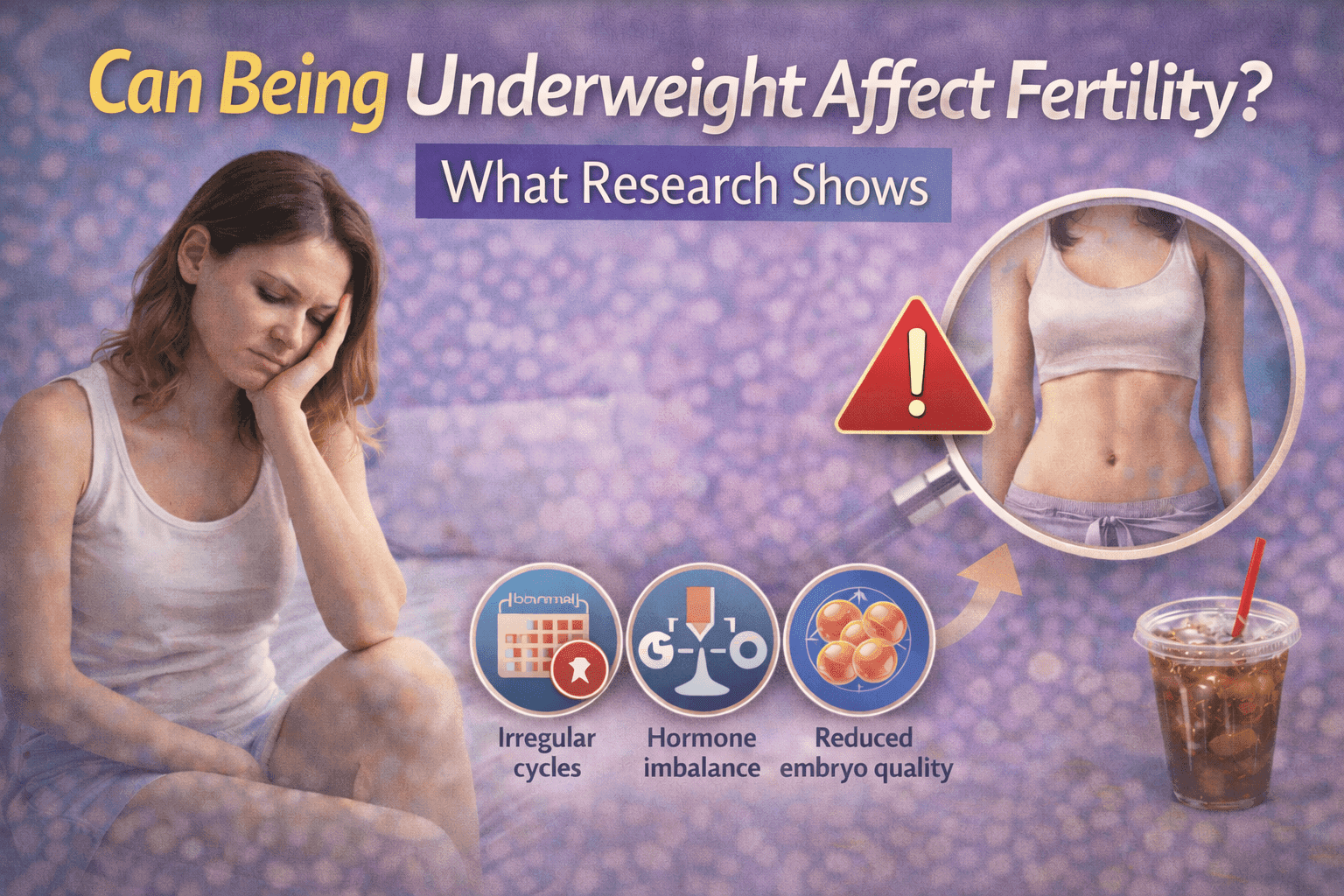

Research shows that body weight and eating patterns influence reproductive health in complex, biologically predictable ways. Being underweight, or consistently eating less energy than the body requires, can interfere with ovulation, menstrual cycles, and hormone balance. This is not about blame or appearance. It is about how the body senses safety, nourishment, and readiness for pregnancy.

Quick Answer: Yes, being underweight can affect fertility. Low body weight or low energy intake can disrupt hormone signals from the brain that regulate ovulation, leading to irregular or absent periods and difficulty getting pregnant. In many cases, restoring adequate and consistent nourishment allows ovulation and fertility to return, although this process takes time and must be approached carefully.

Fertility Starts in the Brain, Not the Ovaries

Ovulation does not begin in the ovaries alone. It begins in the brain.

Female fertility is regulated by the hypothalamic–pituitary–ovarian (HPO) axis, a communication network that integrates information about energy availability, stress, sleep, illness, and nutrient reserves. This system continuously evaluates whether conditions are safe enough to support reproduction.

When energy intake is low or unpredictable, the brain reduces signals that stimulate ovulation. Periods may become irregular, lighter, or stop entirely. This condition is known as functional hypothalamic amenorrhea (FHA).

FHA is not a disease. It is a protective response. Pregnancy requires sustained energy, nutrients, and physiological stability. When the body perceives scarcity or chronic stress, it prioritises survival over reproduction.

Underweight, BMI, and Fertility: What the Evidence Shows

Women who are underweight, often defined as having a BMI below 18.5, have a higher likelihood of ovulatory dysfunction, missed periods, and reduced chances of conceiving. However, BMI alone does not explain all fertility problems.

Some women have a BMI within the “normal” range yet experience disrupted ovulation because their energy intake does not match their level of physical activity, stress, or metabolic demand. This state is referred to as low energy availability.

Low energy availability can develop gradually and often goes unnoticed. It may occur when meals are skipped, portion sizes remain small, carbohydrates or fats are avoided, exercise volume is high, or mental stress around food and body weight is persistent.

In fertility clinics, this pattern is increasingly recognised in women whose test results appear borderline or inconclusive, sometimes falling under the category of unexplained infertility, where cycles are irregular despite no obvious structural abnormalities.

Functional Hypothalamic Amenorrhea Explained

FHA is one of the most common but underdiagnosed causes of infertility in women with low body weight or restrictive eating patterns. It is characterised by reduced secretion of gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) from the brain, which leads to low estrogen levels and suppressed ovulation.

Importantly, FHA can occur even when a woman looks healthy, exercises moderately, or eats “clean.” The body responds to perceived energy sufficiency, not social norms or appearance.

Periods that are irregular, very light, or absent are a key signal. It is important to distinguish FHA from other causes of cycle disruption, such as irregular or absent periods related to hormonal conditions like PCOS, as management strategies differ.

Eating Disorders, Restriction, and Fertility

Eating disorders and restrictive eating patterns have a well-established impact on reproductive health. Women with current or past anorexia nervosa, atypical anorexia, orthorexia, chronic dieting, or long-term fasting are at increased risk of ovulatory suppression and infertility.

Even after apparent recovery, the reproductive system may remain sensitive to stress or subtle energy deficits. This does not mean recovery was incomplete. It reflects how strongly the body learns to prioritise survival when energy has once been scarce.

For many women, fertility challenges can reactivate difficult emotions related to food, control, or body image. This is why fertility care must include psychological safety, not just nutritional advice.

Why Fertility Treatment Cannot Bypass Undernutrition

Some women assume fertility treatments can override problems related to low body weight or restrictive eating. Evidence does not support this assumption.

Studies show that women with low energy availability often have fewer eggs retrieved during stimulation, a weaker ovarian response, higher rates of cancelled cycles, and lower implantation rates. Hormonal medication cannot fully override the brain’s safety signals.

This is why clinics often recommend addressing nutritional status before or alongside fertility treatment options, including IVF. Understanding the IVF process makes it clear that success depends on the body’s readiness, not medication alone.

Pregnancy at Low Weight and the Baby’s Health

Adequate nutrition before and during pregnancy is critical for fetal development. Research consistently links low maternal weight and undernutrition with higher risks of preterm birth, low birth weight, restricted fetal growth, and increased susceptibility to metabolic and cardiovascular disease later in life.

These findings are part of the developmental origins of health and disease framework, which shows that early nutritional environments influence long-term health trajectories.

This is why maternal nutrition before pregnancy matters not only for conception but for the lifelong health of the child.

“I Look Healthy”: Why Appearance Can Be Misleading

Many women struggling with fertility say they eat well, exercise, and feel healthy. All of this can be true, and fertility can still be affected.

Reproduction requires sufficient body fat to support estrogen production, stable blood sugar, adequate intake of fats, protein, and micronutrients, and a nervous system that does not perceive ongoing threat.

Looking healthy is not the same as being metabolically nourished. Fertility resumes when the body feels safe, not when it looks a certain way.

Is Weight Gain Always Necessary to Restore Fertility?

Not always, but increased and consistent energy intake usually is.

For some women, fertility returns with more regular meals, larger portions, reduced exercise intensity, and improved sleep. For others, modest weight gain is part of restoring normal hormone signalling and ovulation.

Weight is a marker, not the goal. The goal is biological safety and stable hormone regulation, a principle also emphasised in discussions around hormone regulation in women.

Protecting Mental Health During Fertility Care

Advice about weight can be emotionally triggering, particularly for women with a history of eating disorders. Fertility care must avoid pressure, fear, or shame and include psychological support where needed.

Changes should be gradual, medically guided, and respectful. Pregnancy should never require relapse or loss of emotional safety.

Can Fertility Return With Adequate Nourishment?

In many cases, yes.

Research shows that restoring energy availability and reducing physiological stress can restart ovulation, normalise hormone levels, improve treatment outcomes, and reduce pregnancy complications. Recovery is rarely immediate. The body often needs months of consistent nourishment to regain trust.

You Are Not Alone in Asking This Question

Many women hesitate to ask whether they might be too thin to get pregnant because the question feels personal or shameful. It should not.

Undernutrition is shaped by culture, expectations, trauma, and past illness, not failure. Fertility challenges are signals, not punishments. The body does not resist pregnancy. It waits.

FAQs About Being Underweight and Fertility

Can Being Underweight Stop You From Getting Pregnant?

Yes. Being underweight can stop ovulation or make it irregular by disrupting hormone signals from the brain. When energy intake is too low, the body prioritises survival over reproduction, making pregnancy harder to achieve. Restoring adequate nourishment often helps ovulation return.

Can You Get Pregnant If You Are Underweight?

Yes, some underweight women do get pregnant naturally. However, the likelihood is lower if periods are irregular or absent, which is more common at low body weight or with restrictive eating. Fertility improves when energy intake becomes consistent and sufficient.

How Underweight Is Too Underweight for Fertility?

A BMI below 18.5 is associated with higher fertility problems, but BMI alone does not tell the full story. Some women with a higher BMI can still have fertility issues if they are under-fuelled for their activity level. Energy availability matters more than a single number.

Does Not Eating Enough Affect Ovulation?

Yes. Consistently eating too little can suppress the brain signals that trigger ovulation, even if body weight appears stable. This condition is known as low energy availability and is a common cause of cycle disruption. Regular meals and adequate intake are key for recovery.

Can Exercise Cause Infertility If You Are Thin?

Exercise itself does not cause infertility, but high activity without enough fuel can. When energy output exceeds intake, ovulation may stop as a protective response. Balancing exercise with proper nutrition supports reproductive health.

What Is Functional Hypothalamic Amenorrhea (FHA)?

FHA is a condition where ovulation and periods stop due to low energy intake, stress, or excessive exercise. It is one of the most common causes of infertility in underweight women. FHA is often reversible with adequate nourishment and reduced physiological stress.

How Long Does It Take for Fertility to Return After Weight Gain?

Fertility may return within a few months once energy intake is adequate and consistent, but timelines vary. Hormone levels and ovulation often stabilise gradually rather than immediately. Patience and sustained nourishment are important.

Can Fertility Treatment Work If You Are Underweight?

Fertility treatment is less effective if the body does not feel adequately nourished. Hormonal medication cannot fully override suppressed ovulation caused by low energy availability. Many clinics recommend improving nutrition before or alongside treatment.

Does Being Underweight Increase Miscarriage Risk?

Low body weight and undernutrition are associated with a higher risk of miscarriage, particularly in early pregnancy. This is thought to relate to hormonal imbalance and nutrient availability. Many underweight women still have successful pregnancies with proper support.

Can Being Underweight Affect the Baby’s Health?

Yes. Undernutrition during pregnancy is linked to low birth weight and preterm birth, and may influence the child’s long-term metabolic health. This is why improving nutritional status before conception is strongly recommended.

How Conceivio Supports Women

At Conceivio, we understand that fertility, nutrition, and mental health are deeply connected. For women who are underweight or have a history of restrictive eating, we offer evidence-based education, gentle guidance focused on safety rather than weight targets, emotional support alongside fertility goals, and thoughtful fertility care planning that respects both physical and psychological wellbeing.

The goal is not control. It is helping the body feel ready.

Key Messages to Remember

- Yes, it is possible to be too under-nourished to get pregnant

- Fertility depends on energy availability and biological safety

- Restrictive eating and eating disorders strongly affect ovulation

- Low maternal weight can influence pregnancy and child health

- Recovery should always be compassionate, gradual, and supported